_

When I first met Alice Yuan, I had been living and working in China for just under two years. The company I was working for at the time was just about to close my branch, and transfer me to Alice’s, and we were introduced in a bar that doubled as a music venue in the eastern city of Hangzhou, which is about one hour west of Shanghai. I would come to meet Alice again in that bar a few times over the following years, when I’d find out on the night of a show that she had played a hand in organising and promoting it. At the time of our meeting, we were both English teachers, but promoting music and hosting events has been a passion of Alice’s since university, and, as such, a lot of the limited knowledge I have about Chinese alternative music has stemmed from conversations with her, between classes and out on teambuilding nights in karaoke bars. Through Alice, I learned more about the Chinese punk scene with which she predominantly associates, and of the shifting musical landscape within China. Those conversations were very much water-cooler chat for the most part though, and I wanted to take the opportunity to dig a little deeper into her relationship with music, background in tour and event management, and to pick up further artist recommendations also. These days, Alice is a leading member of the independent collective BORDERLESS波得乐斯, a project which organises shows and events in China, offers promotion for touring artists, and strengthens connections in the underground music scene here.

Note: Links for all of the artists mentioned in this post can be found at the end.

When I moved to Hangzhou in 2018, it was just after graduating from university, and after a couple of years of travelling between my university cities and London, where I often journeyed on weekends to see gigs at any of the countless venues in the capital. From a grassroots survey at the time, London was said to have some 430 such locations. Hangzhou, despite having a bigger population of 12,000,000 people, cannot claim to have anywhere near that many venues. Scrolling through ticketing apps, you’ll see the same three or four repeated, from the bar I mentioned earlier (named Nine Club 酒球会) to the city’s biggest venue, Mao Livehouse, a chain which has branches in several tier-one Chinese cities. This small number of venues wasn’t necessarily a surprise to me when I arrived in the city, but that was only because I hadn’t known much about the live music scene before moving here.

Alice arrived in Hangzhou around 2009, around the time of graduation for herself. “I decided to come to Hangzhou to do a part-time job to earn some money to buy a ticket to see Oasis in Shanghai” she tells me, “but that show was cancelled.” That part-time job was as a waitress in a cafe named Reggae Café, where she eventually switched roles to help arrange and promote gigs in the sister enterprise Reggae Bar. “It was probably one of Hangzhou’s first real venues at the time,” she says. “We hosted a few foreign bands playing rock and roll, and some local bands too.” That year, according to Alice, there were only two places in the city that would draw a crowd for live music, Reggae Bar and a club named Cold Space. Alice soon promoted electronic nights for the latter, sometimes pulling in up to 1,000 people for significant events. Cold Space closed not long after, as a lot of businesses do, due to a lack of investment. “It was such a shame,” Alice laments, “nobody saw the potential.” China at the time, and to a lesser extent now, is not a country in which independent music venues (and independent musicians by extension) can thrive. Though, things have improved in some respects. For example, in the early 2010s, the country only hosted two large-scale music festivals, Strawberry Music Festival, and MiDi Festival, which were hosted in both Shanghai and Beijing. “Only two cities,” Alice tells me, “and they were competitors too.” Nowadays, there are far more local festivals taking place, from city to city, and the audience for those shows has changed also. “Before, our market was mainly just westernised Chinese people, and foreigners,” she explains, but a recent uptake in the number of people interested in live music has made for more opportunities to promote and put on shows. This has led also to the increase in the number of venues too, with brands like Mao recognisable across the country.

“Before, there were no venues, not really! Bars were more popular,” Alice recalls of her early days in Hangzhou. “These days, I think China is more similar to the UK, in that younger people are going out and seeing shows.” Her target audience has moved from foreigners to the local youth, Chinese students or post-grads between the ages of fourteen and twenty-four. Something has shifted, and led to that increase in interest, and Alice attributes a lot of it to TV, namely talent-based shows hosted and produced by Ma Dong 马东, former Chief Content Officer of online video platform iQiyi 爱奇艺. “Chinese media started to produce more reality shows – all kinds,” Alice expounds, “some were about hip-hop, some were about parenting, and some were about stand-up comedy. New culture, we called it. We started to want to promote culture more, including rock and roll.” The ‘we’ she refers to here seems to be China collectively, and music appreciation is seen as part of this push. I recall seeing the 1998 movie ‘The Legend of 1900’ in a Wuhan cinema in 2019, twenty-one years after its initial release. The movie tells the story of an extraordinarily talented pianist, played by Tim Roth, born on a cruise ship and destined never to leave. There was something strange about seeing a film like that, in that year, in that landlocked city especially – Wuhan pre-2020 being best-known as the birthplace of China’s punk scene. The movie was sold out, and the bar show I attended the night after had sold plenty of tickets also.

‘The Legend of 1900’ is a distinctly American movie, perhaps re-released in the absence of China having a movie of its own in a similar vein. The New Culture that Alice mentions does inevitably borrow from western influences, for both better and for worse. “There were a lot of bands on these TV shows who did just sound like they were copying Oasis,” she says. Another complaint she has is that the TV shows of that period, such as ‘The Big Band 乐队的夏天’ took already established and relatively successful bands who had faded from the spotlight and repopularised those artists, especially in the earlier seasons. “I was listening to those bands at university,” she grumbles, “bands were chosen based on their existing fame. Most of them were just old bands getting famous again.” Some of these bands had been on hiatus, or had disbanded prior to the call-up, and so were playing old songs, which Alice feels “didn’t really fit the time anymore.” Despite these TV shows drawing more attention to alternative music, or rock and roll, Alice explains that the intended audience was mostly still a mainstream one, and that the underground, which had existed before and after, didn’t really get a look in.

However, she concedes that “young people know what’s good,” and that TV shows like ‘The Big Band’ offered a way in, and a prompt way out towards better sounds. For a lot of the curious youth, this involves going to shows, and of searching for music online. But then, the question is of how. China is notoriously a place that draws down the internet shutters on the outside world, with a lot of sites inaccessible from within the country, without a VPN or a workaround. I think of myself when younger, browsing through copies of Kerrang! and NME in newsagents without paying for them first, or scouring platforms like Limewire and Myspace into the early morning most nights in search of gold. I fail to imagine how music seeped into China from other continents, and it’s something I have to ask Alice about, regarding just how she came across Oasis, prior to that cancelled Shanghai concert. “I witnessed the history of rock and roll in China,” she says proudly in response. “We didn’t have much of a platform for finding rock and roll music as teenagers, there was an illegal business which helped. People would import ‘trash’ to China, CDs that were cracked and damaged. The companies or record labels, if they didn’t manage to sell all of their stock, would try to destroy those CDs. But, if not completely destroyed, some would be salvaged. Maybe on one album, from ten songs, you could still listen to eight of them.” Her eyes glaze over slightly at this point, reminiscing. “I would go to the stores run by those bulk-buyers, and listen. That’s how I found Oasis, Blur, Gorillaz, Green Day, Simple Plan, and Linkin Park – those kinds of bands.” Those stores weren’t always easy to seek out – Alice uses the word “hidden” – but says vendors would sometimes tour the city universities, and she would rush out to meet them on arrival. For these vendors, she notes, around half seemed to be in it for the money, while half were genuinely passionate about the music, and were always full of recommendations. Outside of physical media, she mentions a platform named ‘Electric Donkey’ (电驴), which sounds in some ways similar to Limewire.

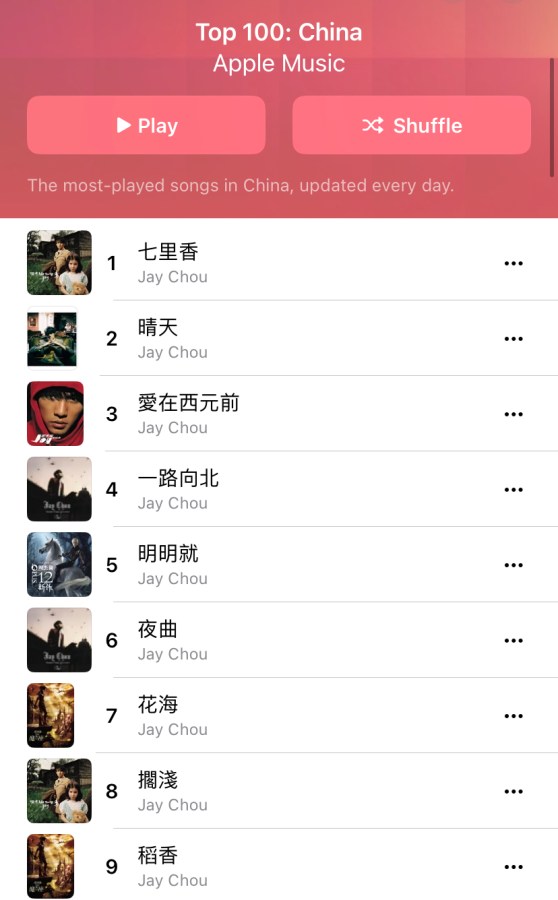

And so Alice became immersed in indie and indie-rock, managing the let-downs of cancelled concerts from big-name British bands, and playing the music video for Blur’s Coffee and Tea on repeat. When asked for a list of bands she likes, Alice rattles it off quickly, with names new and old, and, in this way, she is unlike the majority of my current students. I teach in a local university, and often try to engage classes with music, and music as such is a recurring topic of conversation. It’s rare though that I meet a student who cares for or knows music the way Alice does, and this doesn’t come as a surprise to her. “People here mainly say ‘I like music,’ or ‘I listen to music,’ but I don’t really know that they do,” she says. I hear the same responses in my classes, and, when prompted with follow-up questions, students tend to list genres, instead of artists. This goes beyond the firewall issues, and seems more an indication that people care more for types, than they do for specific musicians. “People just listen to whatever is thrown at them,” Alice adds. We speak about streaming platforms like Apple Music, and I skim the ‘Daily Top 100’ for China with purpose, finding that it’s dominated by Jay Chou songs primarily. There’s some JJ Lin in there, some Eason Chen, two Taylor Swift songs, and some K-pop also. It doesn’t make for a particularly diverse list, and Alice suggests this lack of variety in the Chinese mainstream stems from childhood, and the way in which not just society, but also the schools, approach music. “There was a guitar club at my university,” she tells me, “but it wasn’t very good, and didn’t bring many people in. We didn’t have many communities related to music.” These clubs, student-run, are unlikely to develop beyond a core group of key members, and, factoring in students’ workloads and other pastimes, such clubs might not be well-attended in the long run. That’s not to say there isn’t space for music at a typical Chinese university. At my own, a festival of sorts was held on a recent Saturday, in which student bands and musicians performed. However, these sorts of events are far fewer in number than the competitions, debates, and other performances that occupy the calendar of the average student.

If these clubs and communities are difficult to find even at universities in large cities, then they are almost impossible to find in the smaller cities and towns, or in the suburban districts on the outskirts of major cities, where venue scarcity is another concern. Alice is from such a district, close to the end of the local subway network, and bemoans the state of the music scene there. “Even now, there’s no live music, no venues,” she says, “there are hundreds of kids who would love to go to shows, but can’t. It’s a dream for them.” This has always been the case, and she’s pessimistic about change. “I think it depends on government policies,” is her response when I ask about the future of venues both small and large. “If they want to encourage rock and roll culture, or suppress it, that’s what decides,” she adds, “no matter what though, underground music will always be there.” She is optimistic though about the role the internet plays in terms of exposure for local and China-based bands, and for the opportunities it presents to bands looking to find exposure on the international stage. We speak about a couple such bands, Chinese Football primarily, who, at the time of writing this, are engaged in a UK/European tour, and have had recent LPs sold by international distros like the excellent Dog Knights Productions. Hailing from Wuhan, the band have drawn plenty of attention from the west, initially due to their name (a clear reference to American Football), and then due to the quality of their music, a delicate blend of indie and Midwest emo, full of twinkly guitar work and bright melodies. For local bands with similarly international ambitions, Chinese Football are the framework, and it leads me to question Alice about the importance of names, in terms of pulling in foreign listeners. “It’s good for them,” she says, “because musicians need to make sure they share and get people into their music; the name is part of the method.” It works both ways too, she notes, in that bands with foreign members can take on Chinese names in order to draw attention in China also, such as math-rock band Shanghai Qiutian (Shanghai Autumn / 上海秋天).

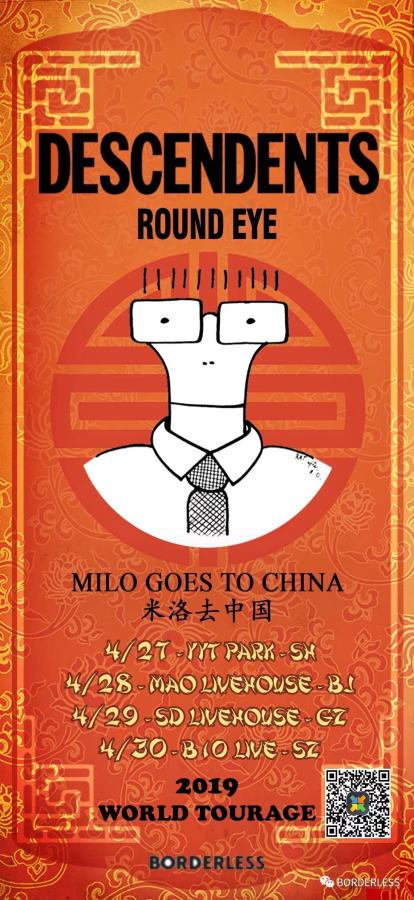

What seems increasingly true, despite recent touring setbacks related to COVID, is that there is an audience for foreign bands within China, just as there is a growing audience for Chinese bands outside of China. Alice has played a part in organising runs and shows for a number of international bands touring within China, including legendary American punks Descendents, who played four Chinese shows in 2019 – their first in the country. Alice remembers them fondly – “they were real punks! They came as a tiny group, just for the fun of it.” She describes the shows beaming, even when detailing missed trains and ticket pricing discord. “I respect that they wanted to keep ticket prices low,” she says, tricky when accounting for flight costs and other administrative factors involved when American bands tour Asia. “We missed a train from Shanghai to Beijing,” she recalls, “but nobody in the band complained, and they were really patient. They were such hardcore punks even in their sixties, and such nice people too.” She believes that the current Livehouse bosses and those in the upper tiers of the industry could learn a lot from the punk ethos and approach to touring, both American and Chinese. Doing so, for her, seems the best way to move forward, and to ensure mutual growth without the excessive compromise of values. “If they see there is potential, if they see there are audiences that want to come to shows, and want to experience new music, then maybe something happens,” she explains. “Why can’t the venues and record labels communicate with young audiences?” At the moment, there does seem a disconnect between the attendees and management, and the underground remains firmly confined to the underground. “There needs to be some kind of outside influence,” she goes on to say, “and there should be more funding for alternative music, like there is for classical and traditional music.” For her, this extends to schools and universities also, the clubs and the classes. It’s a matter of money too, making tickets more affordable for the current generation, who are struggling with job competition and low salaries. “So many shows these days are like 200 or 300RMB (equivalent to around 28-40USD), which is pricing many people out,” she states. “It’s just taking money out of people’s pockets. Venues only care about making money now. We don’t know if anyone cares enough for the industry to prosper and grow. That’s my main complaint, and I think a lot of bands feel similarly.”

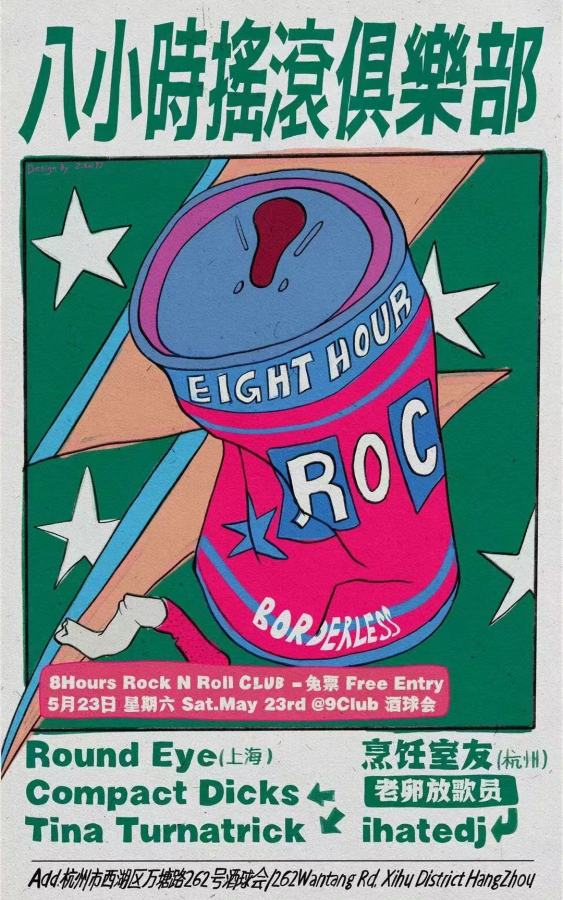

These complaints are valid, for both audiences and for artists, the latter of who, like many western bands, are not making anywhere close to a decent income from streaming services like NetEase Music. Alice shares an anecdote about a local band she saw interviewed by employees from the platform, explaining that they only make about 5RMB (the equivalent of 70 cents) from a month of streams. She’s glad that such interviews and research is taking place, but feels there needs to be action as a result. “I wish I could find a way to show the label bosses some of our shows, to show them what exists,” she says, “to show them what real live shows and bands can be like.” The shows that Alice organises and promotes are of differing scale, and she prefers longer bills, often pushing ‘eight-hour shows’ that involve a host of bands, with adjacent activities taking place within the venue. Such shows are welcome additions to the city listings, in which a lot of concerts only feature a one-band bill. Several of the gigs I’ve attended in China have been without any opening acts, and this seems common for bigger bands; Alice attributes this to the fact that a lot of venues in China “don’t really know how to do shows.” She goes on to explain that, “everything is still quite new, within the scene, and a lot of people in the industry don’t care about the live experience, as long as money is coming in. Even if there’s only one band, people pay anyway.” For her, “a real rock and roll scene would think about how to help new acts, but we don’t really have that culture here. When I worked with foreign bands, they were quick to tell me how we should arrange shows and tours, and we’d always find a support band and pay them.” She follows this by saying that a lot of bands don’t pay for supports, seeing exposure as payment enough.

Similar problems exist, of course, outside of China too. Venues taking merch cuts, streaming services handing out pennies per play, and executives banking on established and legacy acts over emerging talents are not issues confined to a single domestic scene. These days Alice is focused on doing what she can to mitigate some of these negative factors and help to foster a collaborative communal underground scene within China – despite the difficulties that involves. Things are changing, but nothing happens overnight. Still, there is a wealth of talent and quality within the scene, waiting to be discovered and appreciated by audiences both local and international, and I end my conversation with Alice by asking for recommendations. As always, she is quick to offer some, naming the likes of Gum Bleed, Dummy Toys and Demerit as a good gateway into Asian punk. I add them to the list of artists she has sent my way over the years, and, for the sake of this article, will add a few recommendations of my own also, below, in hopes that some might be of interest.

As with all of my discussions with Alice about music, I leave knowing a little more about the music scene within China, with questions answered and new questions generated. Those I do now have can wait for next time, perhaps when we cross paths again in a bar that doubles as a music venue. Hopefully, we’ll do so as part of a growing audience more receptive to alternative music, and an audience better recognised by those who play a significant part in shaping and growing the industry here.

*

Alice is available to assist musicians looking to tour in China, and can be reached for enquiries via email at: Aliceyuanting@163.com

*

Bands 乐队 mentioned, with links to Chinese platforms (though some can be found on Apple Music / Spotify / Bandcamp also):

*

Recommendations from Alice:

The Devils & Libido (Japan)

*

Recommendations from Craig:

草东没有派对 No Party for Cao Dong (Taiwan)

康士坦的變化球 Constant & Change (Taiwan)

*